Note: The following piece on marketing research and social media is co-written with Donnell Wright, VP Strategy & Business Development, Social Intelligence at SDL plc. The proliferation of data science or Big Data analytics presents the field of marketing research with disruptive innovations that most marketing researchers are unprepared to adopt. The analogy for student success analytics and institutional effectiveness officers is briefly considered in a postscript at the end.

Marketing Research and Data Science

Scene: a group of brand managers bring a woman to a market researcher, each claiming her as a customer.

Market Researcher (MR): How do you know she’s a customer?

Brands: She has my customer profile!

Woman (objecting): It isn’t even my profile. They made this profile for me. It is a false one.

MR: Well, then, whose customer is she?

Brands: She’s mine! She’s mine!

MR: Hold on. We have ways of knowing whose customer she is.

Brands: You do?

In the 2015-16 Research SourceBookTM from Quirk’s Marketing Research, only a handful of the listed market research vendors provide descriptions of their services that reference the supply of data mining (6), Big Data (3), or data science (2) services. About fifteen cite social media in their descriptors and a little more than twenty-five enter their firm name under the service category of “social media research.” Of the thousands of companies recorded in the SourceBook, very few provide direct indication of the capability to provide research utilizing the latest methods.

By contrast, in a recent insights report on Big Data and analytics, VentureBeat estimates that brands plan to increase spending on “marketing analytics” by more than 70% during the next three years. Harvard Business Review, citing the CMO survey, suggests similar increases in the share of budget expenditures for marketing analytics and calculates that the brands that adopt marketing analytics will realize greater ROI on their budgets. In light of the expectations of brands and CMOs, it seems only a half-dozen or so marketing research firms stand to profit from the impending spike in expenditures on data science and analytics in marketing.

The imminent gap in expectations for brand marketing budgets and the capabilities of marketing research vendors should not come as a surprise to market researchers and brand managers.

Market researchers remain unfamiliar or leery of the new methods and technology of data science. Although Big Data and data science gained currency in business practice over ten years ago, Quirk’s catalog of 5,000+ research articles does not feature a category for either key phrase despite dozens of references in the articles. In addition, the articles that include those references often feature concerns for or skeptical evaluations of data science or Big Data as applied to marketing research. Likewise, Greenbook, which claims to be “charting the future of market research,” irregularly publishes articles with the key phrase, “data science,” and recent hits include articles entitled, “Is Data Science Friend or Foe of Marketing Research?” (Nov. 2014) and “Market Research and Big Data: A Difficult Relationship” (March 2015).

While social media research, the recent origin of Big Data and data science practices, is a featured category in Quirk’s catalog of articles, the majority of articles review social media through the prism of traditional research methodologies. Articles suggest methods to “integrate” or “add” social media to current marketing research efforts, focusing on the use of social media in segmentation, shopping, campaigns, brand tracking, and other routine marketing research projects long-familiar to the industry. In this respect, the adoption of social media data and technology have proceeded to the degree that research vendors have been able to make them conform to established practices and uses.

Unsurprisingly, as VentureBeat indicates in its report, advanced analytic methods associated with data science are utilized infrequently or ineffectively in marketing research. In general, data science in marketing research currently suffers from a lack of adoption, wariness for the implications to the marketing research industry, and engaged only to the extent that its social media data may be analyzed within traditional frameworks. Thus, while marketing researchers anticipate data science to influence the future of their profession, few vendors have grasped exactly how data science redefines the entire portfolio of marketing research services and insights.

Marketing researchers have well-established “ways of knowing,” and vending, to brands and clients. Data science enters the scene as a challenge to the current ways of knowing customers and vending marketing research projects to brands. To be sure, data science requires investment in new technologies, the adoption of machine-learning algorithms and techniques, and a commitment to continuous research with a dynamic, unstructured data set. Nonetheless, if marketing researchers continue to increase their supply of data science under the current terms, brand executives will likely seek other vendors and professional data scientists to meet the growing demand for marketing analytics that promise the discovery of new ways of knowing their customers.

Seeing the Shift for the Paradigms

Continuing the exchange between brands and a market researcher….

MR: What do customers do?

Brands: They buy things! The buy things!

MR: Correct. And, why do customers buy things?

A brand: They have disposable income?

A second brand: They cannot make things for themselves?

A third brand: Because they prefer me!

MR: That’s it: preference. Now, has this customer purchased from any of you?

A brand: No.

A second brand: I do not know.

A third brand: She walked past my store…

MR: OK, she has not purchased anything, so we do not know which of you she prefers.

For market researchers, data science will entail a paradigm shift in the theoretical sense outlined by Thomas Kuhn. Paradigms hold a priority over research practices because one of the problems that paradigms first solve is the designation of what constitutes the “class of facts” that represent the “nature of things.” In this respect, the paradigm structures research practices by guiding what passes as fact, what stands as the next problem to solve, how to approach a solution to the problem, etc. The choice of paradigm “is not and cannot be determined merely by the evaluative procedures characteristic” of an existing research practice, because a research practice invokes ”its own paradigm to argue in that paradigm’s defense.”

Considering the tenor and content of the articles at Quirk’s and Greenbook mentioned above, marketing researchers continue to regard data science as foreign to the current paradigm, while others have attempted to evaluate data science within the norms and criteria of typical marketing research projects. In general, few marketing researchers have begun to make the shift between the two paradigms for the investigation of consumer behavior.

Traditional marketing research anchors its projects and insights to the perspective of the point of sale. This simple statement will strike many readers as common sense, unworthy of further consideration. The obviousness of the assertion, however, reflects the priorities of the marketing research paradigm dominant since the twentieth century and its links to a foundational assumption in traditional economic science.

In the language of the profession, for instance, take the difference between the terms, customer and consumer. A simple distinction widespread on the internet suggests the customer is a purchaser of goods and services, while the consumer is regarded as the user of goods and services. While the consumer is the more inclusive term and suggests the ultimate purpose of the purchaser (one family member often purchases for all family consumers), much of marketing research organizes itself around the concept of the customer. As of the writing of this article, a search of the phrase, “customer satisfaction” (in quotes), yields over 80,000,000 hits, while a search of the phrase, “consumer satisfaction” (in quotes), yields a paltry 600,000 hits in comparison, and often to pages containing “customer satisfaction” in the title. Traditionally, marketing research terminology evokes a focus on the various stages in purchasing: mystery shopping, packaging research, customer satisfaction, customer experience, customer loyalty, etc.

While it may be that the terms “customer” and “consumer” are being used interchangeably, the priority of customers over consumers reveals the production-oriented perspective of marketing research. Given the narrow window of the purchase in which to measure the movements and activities of consumers, the activities of producers subtly dominate the perspective of marketing research. In the sixth edition of his textbook, “Exploring Marketing Research” (1997), William G. Zikmund emphasizes the consumer orientation of marketing research and indicates many marketing theorists regard “the satisfaction of consumers’ wants [as] the justification for a firm’s existence.” When he categorizes marketing research, however, his perspective returns to production and he defines marketing research as the study of “each element of the marketing mix” for a specific business: product, pricing, distribution, and promotion research. In this respect, marketing research in fact orients itself as research into the operations and activities of producers, not as research on the markets and activities of consumers.

Prior to the digital age, the producers of mass-marketed goods and services had access to the behaviors of their own customers, by and large, while the behaviors of consumers in general proved to be more abstract. In the interval between two purchases, producers and resellers had little substantial insight into the behaviors of their customers as consumers. In lieu of direct information, consistent with neoclassical theory in economics, marketing research assumes consumers have fixed preferences that yield consistencies in product purchases. This framework considers consumer preferences as individual, fixed, and “elicited” by economic activity, but not shaped by economic activity – that is, exogenous. As legal scholar Cass R. Sunstein characterized the economic premise, “If people are going to select an ice cream flavor, or a television set, or a political candidate, they will consult a kind of internal preference menu, and their choices will result from the consultation.” For marketing research purposes, the purchase decision then served as an incomparable window into the hidden world of personal desires and material needs for products. Marketing researchers then investigate the incidence, segmentation, profile, and intensities of stable consumer preferences for products without much regard for how preferences form.

The oversimplification of consumer activity and purchases as the expression of fully-formed preferences obscures the need to understand directly the social activities of consumers and their recurring construction of preferences. Since economic and marketing theory regarded preferences as exogenous to the economic system, scholars from other disciplines and critics of neoclassical economic theory have been at the forefront of the question of how consumer preferences form.

A critic of the theory of fixed preferences in the early twentieth century, sociologist Thorstein Veblen, analyzed the “conspicuous” nature of consumption in industrial societies. His approach to understanding consumers emphasized the social performance and reputable distinction associated with consumption. Consumer practices take shape as an emulation of customary standards of living, and a canon of consumption forms as a “coherent structure of propensities and habits.” As everyday life grew to include casual and anonymous contact with larger and larger populations, as in urban life, he noted that “the serviceability of consumption as a means of repute, as well as the insistence on it as an element of decency” would increase its effectiveness and become more prevalent in time.

Scholars at the end of the twentieth century extended Veblen’s ideas to encompass the concept of the consumer society. As anthropologist Arjun Appadurai asserts, consumption is “eminently social, relational, and active rather than private, atomic, or passive.” As this statement suggests, social consumption fully inverts the perspective of consumers as motivated by personal preferences expressed in private purchases and fulfilled in the passive use of goods and services. Instead, social consumption focuses attention on how consumers engage products and brands to send and receive messages to others in an unfolding, open-ended dialog about preferences. Consumers in general intentionally construct preferences through all stages of consumption, rendering a single purchase as merely one personal message in the full social exchange of preference construction by consumers. In effect, social consumption transcends the structures of any one market and recognizes the agency of consumers in shaping preferences and brand identities.

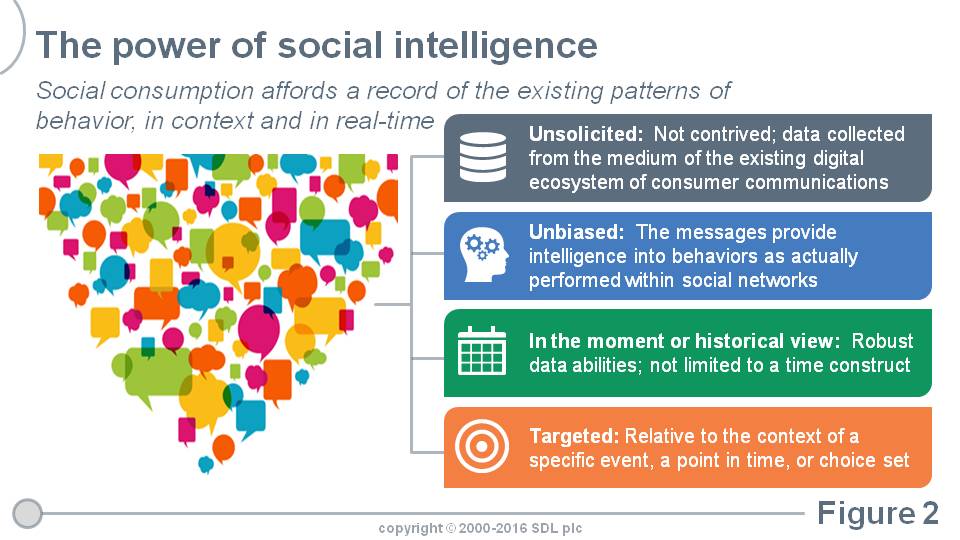

Today, social media creates a vast record of social consumption and the construction of consumer preferences in the context of different environments, languages, and cultures. More importantly, social media is quickening the construction and reconstruction of preferences among consumers as brands are forced to compete for attention against the best brands in all markets and as social consumption becomes unbound by physical, national, and linguistic constraints. The brands that successfully harness the new media will produce unsolicited, unbiased, contextual and targeted insights into consumers and utilize the power of social intelligence to improve the customer journey from brand awareness to brand loyalty to brand evangelism.

Jack Welch once observed, “If the rate of change on the outside exceeds the rate of change on the inside, the end is near.” While the presumption of fixed preferences may be comforting to marketing research, it fails to acknowledge the increasing rate of change for the construction of preferences in the social life of consumers. Social media offers brands and marketing researchers the ability to directly investigate the construction of preferences in consumer markets. Data science using social media media data set allows marketing researchers to focus on the total trajectory of the construction of consumer preferences – from predisposition, through shopping-purchase experience, to social consumption. While each customer has his or her own unique journey with a brand, social media record – in photos, tweets, posts, and more – the communications that make sense of brand choice in the lived experience of consumers.

There is No Outside the Social Media of Consumption

Continuing the exchange between brands and a market researcher….

MR: Aside from preferring things, what else do customers do?

A brand: Complain?

A second brand: Write reviews on Yelp?

A third brand: See advertising?

MR: Okay, they receive advertising.

A brand: I advertise.

Other brands: So do I.

All brands: She is my customer! She is my customer!

MR: Wait, wait. You are getting ahead of yourselves. How do you know she has seen your particular advertising?

A brand: She has eyes?

A second brand: Yes, Yes, she has eyes.

All brands: She’s my customer! She’s my customer!

MR: No, no, no. Where do you see advertising?

A brand: In the bathroom?

A second brand: On billboards?

A third brand: On TV?

MR: Yes, all of those, but most importantly on TV.

The premise of exogenous preferences simplifies the study of consumers as a whole. If preferences are fixed and innate to the individual, the social environment may be regarded as largely static and subject to change at the rate of repopulation. In addition, preferences are discovered or known, not created, so periodic sampling of a population in focus groups or surveys provides the basis for analyzing its proclivities. Preferences may be regarded as transitive, as well, so that knowing one preference becomes grounds for knowing other preferences: customers who buy X are likely to buy Y. In these and many other ways, the presumption of fixed and individual preferences structures the producer-centric perspective for research of the marketing mix: product, price, and distribution.

On the other hand, the concept of promotion extends the breadth of marketing research activities. Despite the fact that advertising takes into account consumers’ receptivity to emotional and social content regarding their consumption behavior, advertising research reinforces the idea that consumers passively receive predefined information regarding products and services. Concepts such as brand image, brand message, and brand identity connote a static set of characteristics designed and disseminated by the vendors of products and services. Advertising in this manner easily slips into the assumption of a unidirectional telecommunication of brand content and a top-down broadcast of brand meaning. The brand, like the product or service, emerges fully-developed from companies’ marketing departments and advertising agencies.

Perhaps the most deficient aspect to the concept of advertising is the original meaning of the term as a turning or diverting of consumer attention, as if consumers engage in consumption inadvertently.

To the contrary, via social media, consumers wholeheartedly direct their attention to the products and services they consume. The content of social media is social consumption and its data set is a digital register of brand engagement and loyalty. Through this lens, we see marketing messages delivered through advertising as singular utterances in non-social channels of media. The use of hashtags, “likes,” and other devices in advertising signals the extent to which social media now overshadows the entire media landscape. Every brand exists in the totality of utterances regarding products and services that consumers post, tweet, like, and broadcast in social media. Brand messaging therefore must be recognized as dialogic and, more importantly, consumers must be acknowledged as active and independent agents in a brand’s dialog. In short, customers have a much greater degree of control over their relationships with brands than traditional marketing research fathoms.

In the dialog of social media, marketing researchers observe consumers dynamically constructing their preferences for products, services, and brands. As Clair A Hill suggests, “The way people make choices and form preferences importantly involves narrative.” These narratives range from simple statements of tastes and enjoyments to describe lower order preferences to complex stories of vision and goal attainment to derive higher order preferences from sustained action or consumption. When preferences are detached from base desires and basic needs that can be expressed in the most common lexicon of consumption, consumers depend substantially on narrative to construct and “entrench” preferences in subjectivity, or the sense of selfhood. Through the frame of narration, preference construction may be seen as a fluid and versatile process of consumer decision-making as they build lives and identities for themselves.

To acknowledge the construction of preferences is to recognize all the world as the stage for social media. The contents of posts and tweets record lines in a play written in the real-time of consumer culture. Situated in the meaningful world of social consumption, the immense data set of personal messages broadcast through social media represents a holistic narrative on the global standards of consumption. These discrete, mercurial expressions of lower- and higher-order preferences nonetheless congeal to form a filigree of conventional expectations that Thorstein Veblen labeled, a “standard of living.” But we should not perceive the standard as given or fixed. A standard of living, Veblen cautions, “is not the average, ordinary expenditure already achieved: it is an ideal of consumption that lies just beyond reach…” As an aspirational momentum, the construction of preferences that forms a coherent standard of living serves as a key exercise in shaping the attitude and decision-making habits of entire customer segments who are blazing their own trails, difficult to predict, and mapping purchasing decisions to fit a future goal.

In this respect, the construction of preferences, while deviating from the notion of fixed and innate dispositions for products and services, becomes the key component in an open system of social consumption with no natural limit on the exchange of information or materials. Whereas spatial and temporal proximity restricted consumer exchanges in the past, such that consumers emulated “the usage of those next above” in their community, social media arrays the multitudinous standards of living in a knotty continuum of reputable and serviceable brands virtually within reach to all consumers. In this respect, purchases that once figured as discrete choices between products and services now factor into preference sets for brands and amenities that signify social standing and personal ambition. In essence. social media delivers the platform for consumers to manage preferences in forums that mitigate decision-making errors due to a lack of information, coherence, time, or judgment. Social media levels the playing field and razes the silos, putting all brands in competition with the customer experience of the best brands across all industries.

Visualized through the prism of preference construction, the social media data set is “unstructured” in a far more profound way than typically understood. The narrative structure and affectations (images, hashtags, emojis, etc.) of consumer preferences defy the traditional data collection instruments of marketing research. As the Harvard Business Review counsels, the unstructured nature of social media data requires investment in unfamiliar technologies to facilitate “advanced analytics and Big Data” and the adoption of methods from human sciences far afield from business administration and marketing. Beyond these considerations, however, social media portend a new capriciousness in the construction of preferences as social consumption challenges the traditional boundaries of place, time, and industry for segments of consumers. In other words, the company executives who assume that preferences are unchanging and finite will find themselves ill-prepared to adapt to a deluge of preference reversals sparked by the viral networking within social media.

If the media is the message, social media is the most profound message since the popular adoption of the television. Marketing researchers must prepare themselves to confront the limitations prior media revolutions have imposed on their vision and utilization of the new media.

To-date, many industries have been insulated from the social media revolution, but make no mistake: the millennials are coming. Millennial consumers will exercise more power over social consumption than any generation in history. As a group, millennials grew up in a world broadcast in social media, came of age while exposed to the continuum of living standards shared in social media, and reached adulthood at a time when the iPhone seemingly placed all products and services at arm’s length. Though currently rooted to age-relevant goods and services, social media irreversibly has shaped millennials’ purchasing behaviors: they see most of what they want as “within reach” while regarding their engagement with brands as a two-way street. A whole generation of “mantle wearing” millennials have established the “Digital Age” pathways to brand engagement and loyalty in social media. The mellinnials’ pathways for the customer journey will influence preference construction for several generations to come – and determine the brands that have value in the new era of social media.

Beyond the Market: Consumer Preference Unbound

Continuing the exchange between brands and a market researcher….

MR: If customers see advertising on TV, logically….

A brand: If this woman owns a TV, then she has seen my advertising…

MR: And, therefore…..

A brand: She is my customer!

All brands: My customer!

MR:. Very good. We shall now conduct unbiased research to determine whose customer she is.

MR (turning to the woman): Ma’am, do you own a TV?

Woman: Well, of course.

Brands: My customer! My customer!

A brand: Download my app!

A brand: Like us on Facebook!

To be clear, the notion that preferences form outside the market remains unchallenged. Preferences originate exogenous to the economic system and the influence of preferences on decision-making tacitly recognizes the agency of consumers. In substance, the study of consumer preferences is beyond the study of markets – i.e., metamarket analytics. The challenge for traditional marketing research rests, more so, in a correction to the oversimplification of preference construction prioritized by the marketing paradigm embedded in the telecommunication society. The center (producers / advertisers) no longer broadcasts information to the periphery (consumers). A formerly safe assumption – that preferences are fixed and coherent (the assumption that made the industry of marketing research indispensable to marketing and advertising executives) – now creates a blind spot for the rate of change in preferences recorded in the social media of consumers.

Perhaps one of the more confounding aspects of data science for marketing researchers is its claim as both science and art, as IBM makes clear in its promotional materials. Given the raw, unstructured narratological data of social media, the data scientist must approach research projects in a less formal, less structured manner than the traditional scientist trained in the ideals of clinical methodologies. Like a sculptor, the data scientist begins with a social media data set cut from the totality of social media records, grotesquely combining attributes, and leaden in appearance. The analytical methods of data science chisel the unstructured records to expose the patterns and formal relationships between the attributes in the textual and visual elements. Indeed, the more advanced data scientists endeavor to portray their data visualizations as “beautiful works of art.”

Nevertheless, it would be a mistake to allow the immodest and unsophisticated claims of data science advocates to cloud the perspective of marketing researchers and executives. Scholars have studied the construction of preferences for many years and the emphasis on preference construction in no way diminishes the relevance of purchasing decisions for the understanding of consumer behavior. As Sarah Lichtenstein and Paul Slovic state in the introduction to their edited collection of influential articles, The Construction of Preference, “If preferences are constructed, then decisions are constructed.” As a consequence, theories of preference construction “constitute theories of decision making…” and provide a whole new framework through which to understand purchasing choices. Moreover, as a relatively nascent area of scholarship, no single theory of preference construction will suffice to explain the “huge assortment of situations for which a preference must be constructed on the spot.” As a result, brand executives will continue to need marketing researchers to investigate the nature and conditions of their specific markets and product choice sets.

On the other hand, the academic scholarship on preference construction largely neglects the fundamental transformation of the new media age: social media will replace the role of personal memory in the construction of preferences. According to the theory of “preferences-as-memory,” Elke U Weber and Eric J. Johnson conceptualize preference “as the product of memory processes and memory representations.” The individual consumer, however, is no longer (and never was) alone with his or her memory regarding the selection of goods and services or the commitment to brands. The sites of social media function as consumer preference management systems that supply native processes to record information (ratings), to store representations (images), and to prime decision-making. More importantly, social media records the communications of preferences, not memories, and implies meaning for both the senders and receivers of consumer decisions. A Yelp, a Like, a Follow, a Tweet: each conveys a shared social meaning among a group that values the purchase decision, the brand, and the implied act of consumption, whether directly or vicariously.

Companies and marketers now understand the need to “monitor” social media. Nevertheless, most also lack the interpretive tools to understand what is being monitored in social media – the construction of preferences.

To perform with the agility and flexibility needed to meet consumer journeys and expectations in the world broadcast in social media, brands and marketers must build the intellectual toolkit for a marketing research paradigm that fully grasps the nature and analytical uses of the social media data set. “Thick data,” as the Harvard Business Review suggests, requires the social scientific methods of ethnography, anthropology, and other fields dedicated to the observation of human behavior and motivations. The object of study for marketing research must also change focus, from the relationship between producers and purchasers or resellers and customers, to the relationship between consumers and things: products and brands. These things, however, are not merely objects to consume, but content to broadcast in social media to signify differentiators for the culture, values, and identity of discrete consumer segments.

In the age of telecommunication advertising, brand managers and marketers were unable to account for preferences. The perceived variety in preferences at the level of the individual consumer made the presumption of fixed, coherent, and exogenous preferences an expedient choice for both advertising messaging and marketing research design. The advent of social media turns the tables: competition for customers’ attention crosses product classes, the randomness of customer behavior destablizes price management and elasticity, the elevation of context over channels yields endless confusion regarding distribution strategies, and marketing campaigns thrive or die based on the frequency of re-tweets and hashtags. The adoption of social media portends an era of preference management systems and social consumption that will coalesce into a new century of virtual self-making in consumerism.

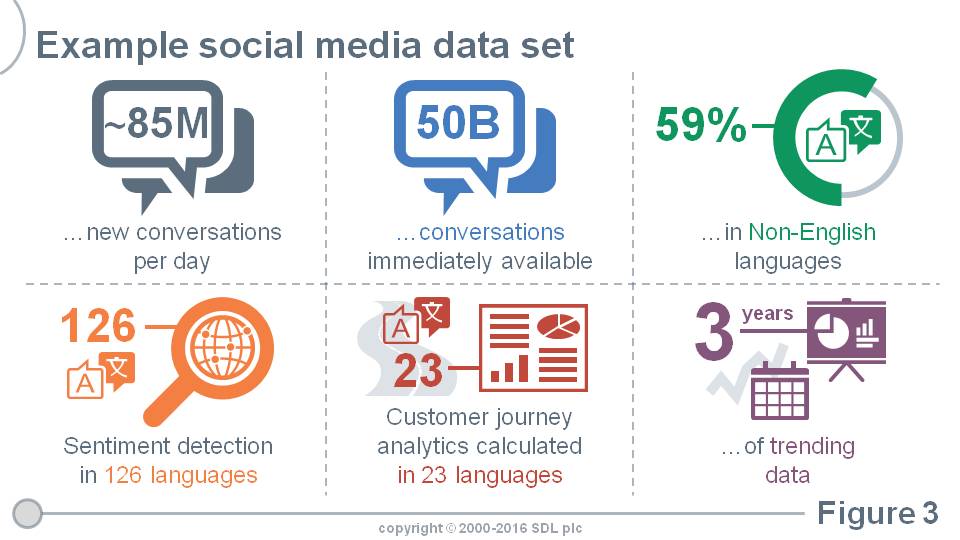

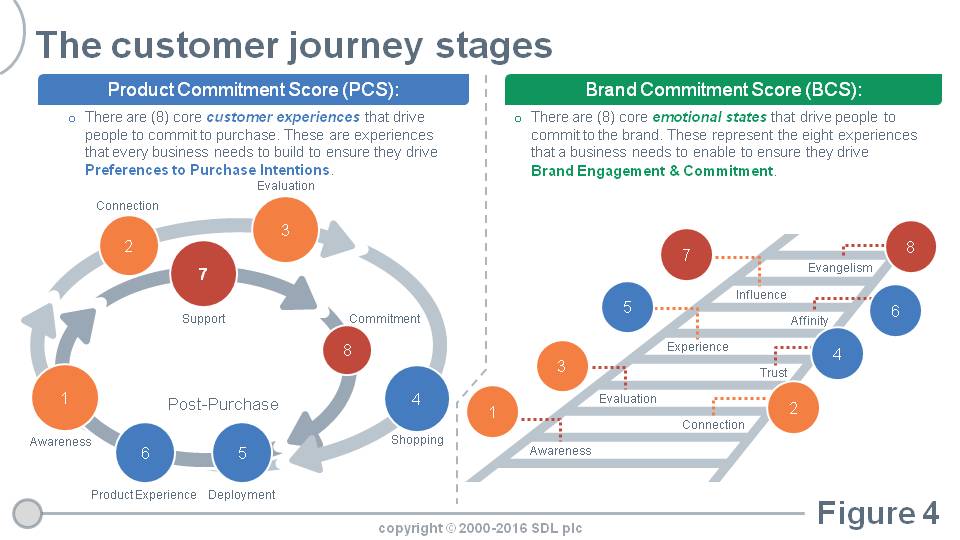

SDL, a social media research technology and solution provider, offers research solutions to identify the construction of preferences in social media and to measure consumers’ product and brand commitments. Like other organizations staking ground at the intersection of Big Data and marketing research, SDL’s adoption of “customer journey analytics” as a vendable technological solution reflects an understanding of consumption as the material for a narrative about consumer preferences recorded and broadcast in social media. Accordingly, SDL’s customer journey analytics incorporate ethnographic methods to score product sentiments, trend brand advocacy, evaluate marketing campaigns impact on the brand conversation, and to extend brand opportunities across markets. Originally a language and digital content solution provider, SDL developed a division (“Social Intelligence Solutions”) to move into the big data and marketing analytics space that traditional marketing researchers failed to stake out for themselves.

The imaginary dialog between a market researcher and a collection of brands paraphrases the dialog in the scene in Monty Python’s Holy Grail when a crowd presents a woman to one of Arthur’s knights as “a witch.” In the exchange, the knight leads the crowd through a series of logical propositions with the intent of establishing an empirical method of determining whether the woman is a witch or not. The Python scene captures, comically, a world in transition between magical thinking (the existence of witches) and scientific thinking (empirical measurement). In other words, a world in transition between two paradigms. The culmination of the movie scene also suggests the catastrophic choices (the burning of “witches”) that decision makers reach when unaware of the cognitive dissonance of two paradigms.

While many marketing research firms make the risky choice to conflate old and new paradigms for brand decision-makers, SDL’s social media research solution exemplifies the priorities of the new paradigm. As illustrated in the the SDL marketing literature featured in the figures above, the construction and lability of consumer preferences as recorded in social media may serve as the primary focus of marketing research. More generally, the literature on Big Data and marketing research foreshadows the inclusion of preference – the construction of preferences – as the fifth facet to a comprehensive marketing mix. The brands that will survive the paradigm shift will be those that measure, refine, and act in accordance to the message of social media and consumers’ ceaseless adaptation of preferences.

Postscript by h | r

Student success analytics in higher education is an industry-specific form of customer journey analytics to study the social construction of preferences. The student journey from college choice, to college degree completion, and eventually to alumni booster is a journey through the stages from brand awareness to evangelism by college-goers.

Unfortunately, institutional research — like marketing research — is wed to the intellectual tools and flawed assumptions of an anachronistic paradigm for studying student success carried forward from the twentieth century. Institutional researchers remain saddled by scholarship and methodologies (surveys) of higher education scholarship that invoke worn and prejudiced concepts — an individual student’s “academic preparedness” and “engagement” — to explain student success. A survey at a single point in the academic year (freshman entrance, NSSE, etc.) rarely serves to improve students’ chances for success. To the contrary, surveys often offer little more than a feedback loop confirming the assumption of “unpreparedness” or “lack of engagement” by the students who do not complete college degrees.

Scholars of preference construction and the methodologies of social media research offer a compelling alternative for institutional researchers who are eager to embrace the data-rich future of higher education. The institutional researchers who adapt to the new paradigm of preference construction and the methodologies of social media research will discover new markers and mechanisms for student success. Likewise, the colleges and universities that directly harness the power of big data and student success analytics will be the ones that thrive into the twenty-first century.

Those that fail to recognize the new paradigm will discover obsolescence in an industry increasingly influenced by for-profit vendors of proprietary technology and analytics for student success.