Outsourcing Student Success | Free Kindle Edition

Thank you for pushing my work, Outsourcing Student Success, to as high as #1 in the Education Theory > Research category and #3 in Higher & Continuing Education on the Kindle Store free edition lists this week.

The FREE Kindle edition special promotion ends today (June 1, 2018). If you have not ordered your FREE Kindle edition of Outsourcing Student Success: The History of Institutional Research and the Future of Higher Education, please visit Amazon.com now.

Please consider reviewing my work on Amazon.com. If you would like to review it in a journal or publication, please contact me for a complimentary hard copy (quantities limited). My argument for why reviews, positive or negative, are in the interest of the profession as a whole is below.

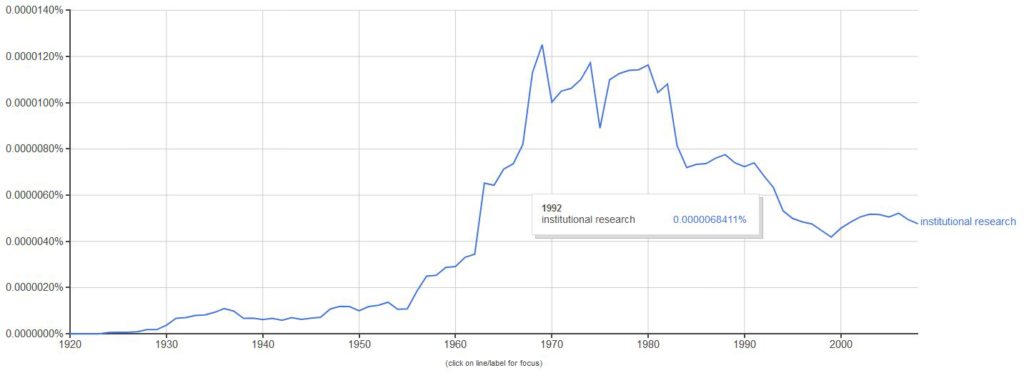

A Google Ngram View of “Institutional Research”

In my work, I outline the 100-year history of institutional research following the establishment of the Bureau of Institutional Research at the University of Illinois in 1918. As the centennial of the first centralized office passes nearly unnoticed by the Association for Institutional Research and the general public, I think it is important to consider the rise and decline of “institutional research” in Google’s Ngram Viewer for Google books.

Although scholars of higher education invented a history of institutional research that supposedly begins at Yale in the 1700s, the phrase “institutional research” clearly does not gain currency until after 1920 (see Figure 1). The dates marking periods of ascendancy in publication coincide with the first institutional research publications analyzed in my work: 1930s following Coleman R. Griffith’s efforts to publicize his work at U. of Illinois; 1955 following the publication of Ruth E. Eckert’s work at the U. of Minnesota and the 1955 California Restudy; 1960 following the American Council on Education endorsement of institutional research and the California Master Plan for Higher Education; and post-1962 bump following Basis for Decision and the first organized institutional research forums.

As I wrote in my work, the central innovation of institutional research – and the centralized offices – was the application of scientific principles to the study of systems of higher education and this innovation in and of itself required public discourse about institutional research.

Figure 1 | Ngram View of “Institutional Research”

Although the incidence of “institutional research” in the public discourse continued to grow for a few years after the formal organization of the Association for Institutional Research, the relative frequency of “institutional research” takes a decided turn after 1968-69, Joe L. Saupe’s year as president of the national association. In 1970, he and James R. Montgomery published “The Nature and Role of Institutional Research” with the endorsement of the association. Use of the phrase suddenly stagnates, with minor ups and downs in an era of “predictable crises” according to Cameron Fincher in 1978. In 1980, the AIR released Saupe’s second iteration of his vision, “The Function of Institutional Research,” and a decline in the prominence of the phrase ensued. Between 1985 and 1991, Cameron Fincher and other scholars redefined institutional research as an art. The AIR released its third iteration of Saupe’s vision and Patrick Terenzini began sounding warnings about the perils of computer technology to our professional development. Then, a second era of decline in the use of the phrase begins and by 1999 the incidence of institutional research in the public discourse fell to 1962 levels.

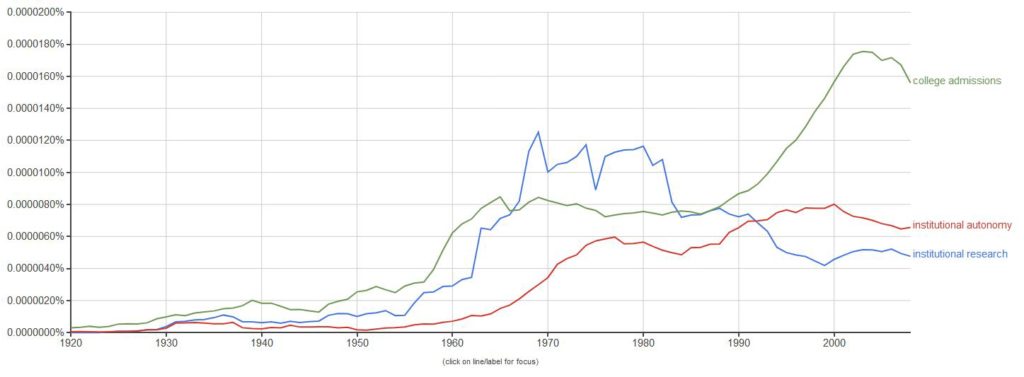

By comparison, two related phrases, “institutional autonomy” and “college admissions,” have more or less increased in frequency since 1960. Although “institutional autonomy” has connections to other industries, the phrase gains relevance only after 1960, as Clark Kerr’s later works suggest, in response to the 1960 California Master Plan and the era of statewide strategic planning that had made system-wide institutional research an annual concern for colleges and universities. “College admissions” stagnated during a time when institutional research contributed to system planning for the Boomer generation, but then escalates after 1985 as Generation X entered college. While the two phrases have their own periods of stagnation, the use of these has trended upward and their incidence in the public discourse is far above their 1962 levels. You might say, the phrase “institutional research,” under the stewardship of a national association (with the very phrase in its title!), has gone missing from the national discourse on higher education.

Figure 2 | Ngram View of “Institutional Research” and Related Terms

I know that some will object to tying the decline of our profession to the stewardship of the national association and its scholars who are so often cited as the academic “experts” in the discipline of higher education for whom we must show gratitude as institutional researchers. As I have noted elsewhere, they will point to some form of technological determinism, administrative contingency, or systemic exigency that places institutional research outside of the control of institutional researchers. The reason, however, that I come back to AIR’s 1970 white paper as a crucial turning point is that it redefined institutional research in a way that dragged it far from its origins. If institutional research emerged from institutional self-study to become the scientific study of systems of higher education, again as I argue in my book, there were many who wanted to shove the genie back into the bottle of self-study.

Saupe and Montgomery effectively redefined institutional research as “within an (one) institution,” thereby ending our collective interest in between-institution research in systems or associations. They claimed, “institutional research should not be expected to produce knowledge of pervasive and lasting significance,” dismissing its potential as a science for the accumulation of knowledge. And they recast institutional research “as a function with a minimum of specific implications for organization,” despite the fact that organization typically is quite dear to disciplines and professions. Their work set us on the path to becoming an insular, unscientific, and undisciplined (i.e., lacking a discipline) profession that has little impact on the public discourse over higher education.

We as practitioners could, as the association does, throw up our arms in hopelessness when the “predictable crises” in institutional research occur every ten years and then republish Saupe’s vision for institutional research as a new vision for the next generation of professionals. I recommend, as an alternative, that we critically review the policies that the leadership of the national association has followed for nearly 50 years and interrogate the scholarship in higher education by members of the faculty who clearly expressed animosity for institutional research at their own institutions and yet had a big hand in shaping our profession. What I was able to uncover in my work is only the tip of the iceberg. There are at least nine areas of further research into the history of institutional research that I can think of offhand (one for each chapter). Reviews will help to isolate the areas of greatest weakness and strength in order to prioritize future historical research as well as other types of investigation. Whether these reviews are positive or negative is of no concern to me. Debate, and acrimonious debate, at least gets our field back into the public discourse regarding higher education in America.

Lastly, I would like to explain one obscure reference in my work: Immanuel Kant’s “What is Enlightenment?” Kant emphasizes that the exercise of one’s own reason must take place “as a scholar before the reading public,” not as a person may engage reason privately “in a particular civil post or office which is intrusted to him” or her. The AIR vision for institutional research is not only an unscientific (at times, anti-science) program for institutional research, it is an unenlightened vision for institutional research as a profession. For too long, we have been advised as institutional researchers to have little regard for more than our civil post or office (“function within an institution”) despite that fact that many of us are enlightened individuals with advanced scholarly degrees. Institutional research may not have a discipline (FYI, by design per Dressel and associates) but most of us do and many at the doctoral level. Consider how absurd it is for a profession or professional association without an academic discipline to profess itself as the expert for the improvement of decision-making in the administration of academic programs and departments. We cannot apply our expertise to the delivery of our own field of study and in our own departments because they do not exist!

Higher education as a discipline or field of study did not exist until the 1970s, only after institutional research faltered. The same scholars who consciously redefined institutional research as an undisciplined profession then consciously redefined their own profession as a discipline and field of study in development. Thus, as Tyrrell had warned in 1962:

Institutional research, throughout American higher education, is now at a point, where a re-examination of concepts, assumptions, and strategy is necessary. Institutional researchers should take this re-examination upon themselves, lest others do it for them.

It is time to reexamine concepts, assumptions, and strategy for ourselves–before the reading public.

Note: Edits after first publication. Brief released prematurely. This work has been updated for clarity and differs from earlier versions posted on LinkedIn and emailed to AHEE.