Waiting for Institutional Effectiveness

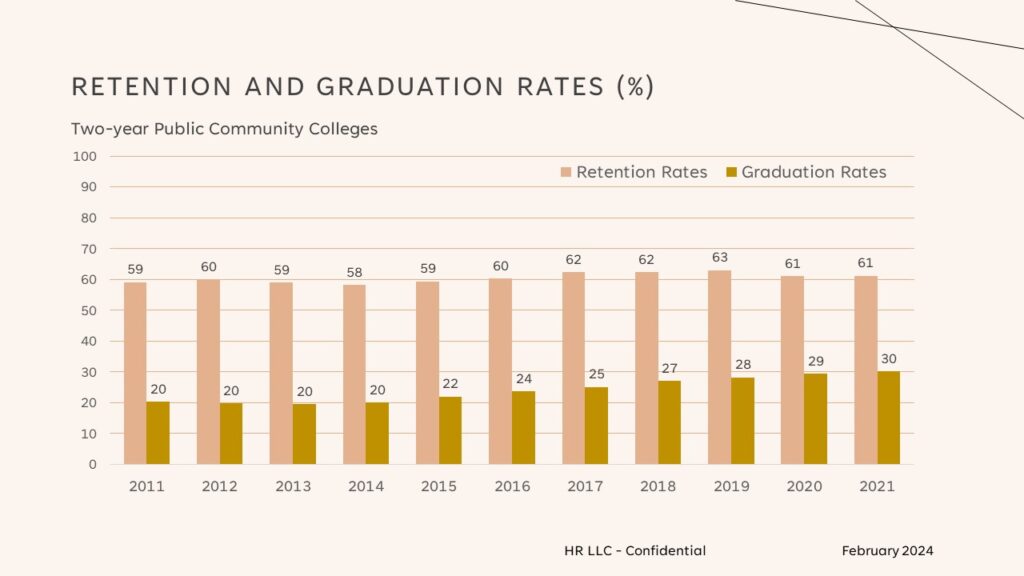

In 2010, after completing a PhD in US History, I returned to college administration as a Director of Institutional Research and Effectiveness at a community college in Illinois. At the time, community colleges were aflutter over Obama’s college graduation goal to “once again have the highest proportion of college graduates in the world.” Several colleges had serious discussions about how to increase college retention and graduation rates, while others strategized how to increase graduation headcounts with procedural or policy changes designed to inflate those rates artificially (by historically acceptable standards). As Figure 1 illustrates, fulltime freshman retention rates at public community colleges have demonstrated no appreciable improvements in the past twelve years. By comparison, the three year (150% of time) graduation rates have climbed steadily since 2013, including the COVID-19 pandemic years. The discrepancy suggests the advocates for procedural changes and certification tricks have largely won the decade. If community colleges have proven unable to attain continuous improvement in first-year student outcomes (retention), should we celebrate improvements in three-year outcomes (graduation) or question whether a new system of inequity in credentialing has been established to reward students who persist into the second year?

Note: All data are from the Integrated Postsecondary Educational Data System (IPEDS).

Figure 1 | National Measures of Public Community College Student Success for Fulltime Students

"A Highly Promising Strategy" for the Nation's Community Colleges

Nationally, the higher education sector has been seduced by news media to believe that a handful of institutions have made significant, evidence-based advances in student retention and graduation rates, whereas other colleges somehow refuse to follow their lead. At the time of Obama’s challenge, higher education news sources and the federal government heralded Kingsborough Community College (KCC) as having created an administrative approach to first-year college education, retention, and graduation that other community colleges should emulate. Its partner, MDRC, “a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization,” promoted and catalyzed interest in KCC at the time and – now – for nearly twenty years (Bloom & Sommo, 2005; Weiss et al., 2022). After two decades, the question is: why are we (and the federal government) so enthralled with MDRC and KCC as a model of improvement for community colleges when so little has changed for retention and graduation rates nationally?

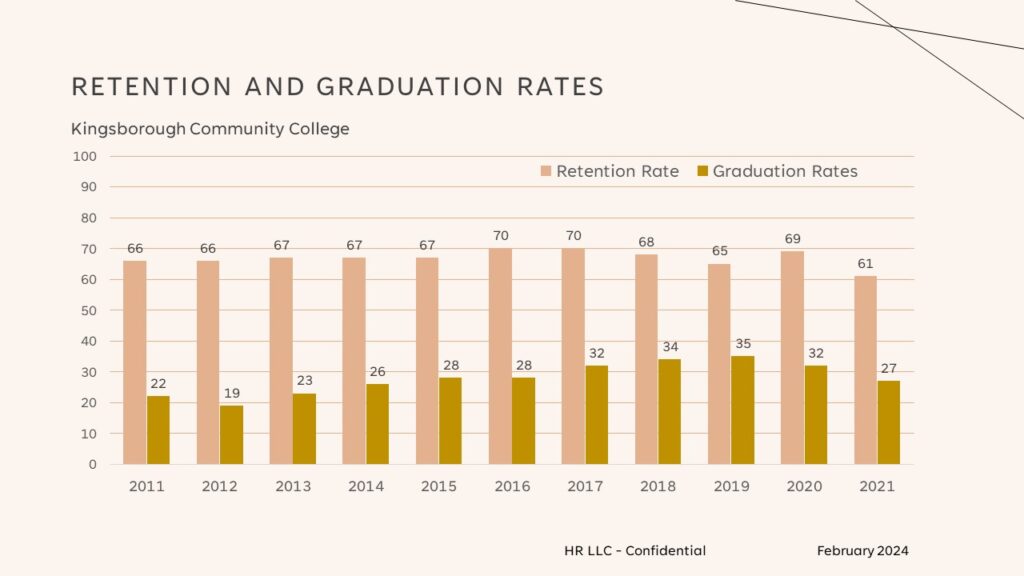

In 2014, I had the privilege of serving at a community college (Prairie State College in Illinois) invited to participate in a Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education (FIPSE) grant project, “The Community College Jigsaw: Putting the Pieces Together,” led by Kingsborough Community College (KCC) of the City University of New York (CUNY) system. I met many dedicated professionals who genuinely believed that KCC as an institution had hit upon a transformative approach to the first-year experience and student success. As the below chart shows (Figure 2), however, MDRC’s research on “evidence-based practices” have had no material impact on student success at KCC in the subsequent decade. In comparison to national trends (Figure 1), KCC is underperforming the entire nation over the past 12 years. No doubt, MDRC will protest that COVID-19 undermined the advances measured by prior research, but retention rates at KCC began falling in 2017. Improvements in the graduation rates improved until 2019 (before a recent decline) but – in the absence of sustained improvements in first-year student retention – the increases for graduations may be the result of credentialing gimmicks as discussed above. KCC apparently reached the limits of generous credentialing after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 2 | Public Community College Student Success at Kingsborough Community College

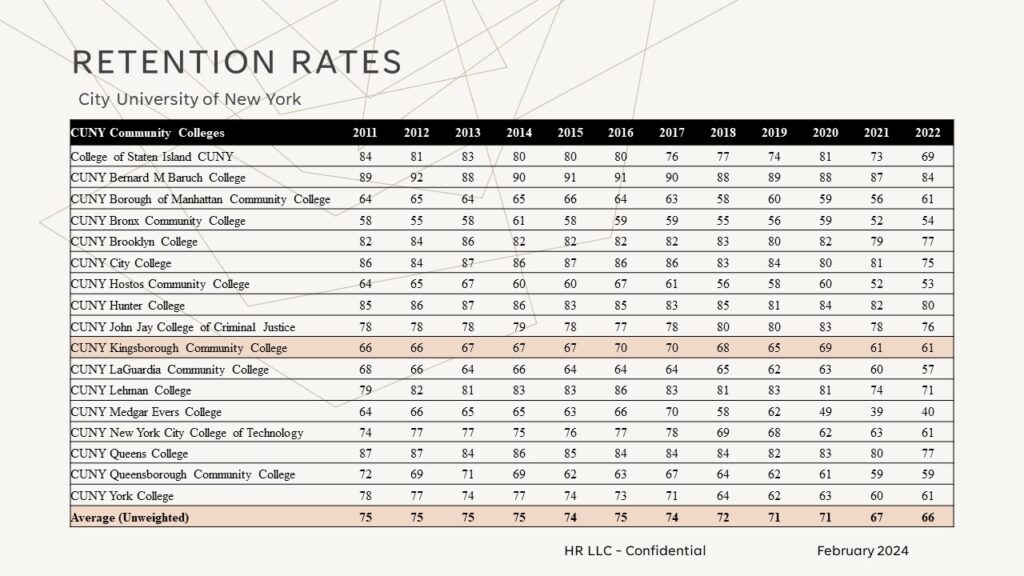

More importantly, in subsequent years, the supposed advancements in developmental education and the first-year student experience at KCC has failed to materialize in the City University of New York community college system. In 2015, MDRC evangelized interventions across the entire CUNY system as strong evidence of the efficacy for student success according to the What Works Clearinghouse based on a randomized controlled trial (RCT). As Figure 3 illustrates, first-year student success (retention) in contrast declined between 2011 and 2022 at every institution in the CUNY system. The average first-time freshman retention rate dropped from 75% in 2011 to 66% in 2022 (unweighted by college headcount). Moreover, the average first-time freshman retention rate in the community college system did not improve appreciably between 2011 and 2017 — the period of time in which MDRC featured the KCC/CUNY approach. Clearly, the assertion that KCC revolutionized developmental learning and the first-year student experience in the early 2000s has been grossly mischaracterized. The supposed transformative innovations at KCC and CUNY had no (or little material) impact on the primary measures of student success for first-year students — retention has hit ten-year lows after dropping since 2017 (pre-pandemic).

Figure 3 | Community College Student Retention Rates in the CUNY System

Department of Education Postsecondary Student Success Grant Awards

During the summer of 2023, the Department of Education announced a notice of funding opportunity (NOFO) for the Postsecondary Student Success Grant Program (PSSG). The grant program sought to “fund evidence-based strategies that result in improved student outcomes for underserved students.” The grant program offered two tracks, Early-Phase and Mid-phase, with the latter expected to yield “‘moderate evidence’ or ‘strong evidence’ to improve postsecondary student success for underserved students, including retention and graduation” according to the What Works Clearinghouse standards. To be eligible for WWC review, “a study must be a randomized controlled trial (RCT) or a quasi-experiment.” Only 3 to 4 awards averaging $7,000,000 over 48 months (4 years) would be available to Mid-phase PSSG applicants in the entire United States (i.e., 3 to 4 awards available for the thousands of higher education institutions in the nation).

When the PSSG announced awardees, City College of New York (CCNY), “a flagship campus of the CUNY system,” earned a $7.32 million grant to “test whether the Open Doors study at Kingsborough Community College…can be replicated in a similar population in a 4-year setting.” Astonishingly, the program referred to — Open Doors — the very same program from the 2005 study by MDRC at KCC that has proven to have no appreciable impact on retention rates at KCC, CUNY, or in the nation. More surprisingly, the CCNY abstract published with the PSSG notice of awards, fails to mention key aspects of the scoring criteria:

- Significance (15 points): CCNY is simply exploring “whether” a twenty-year old intervention (Open Doors) at its “fellow CUNY campus” has potential for “scalablility from a large unit of the college to the whole campus.” In other words, CCNY has no idea if the intervention will be meaningful.

- Strategy to Scale (35 points): CCNY commits to interventions “to meet the RFP’s minimum sample size of 2,000 students over the span of the grant.” In other words, CCNY has no concrete projection for the number of participants in the required RCT and seeks only to meet a minimum requirement.

- Project Design (15 points): The abstract vaguely describes how “existing programs…will be adjusted to incorporate cohort-based learning…[a]dditional advising and dedicated tutoring…” Does that level of detail routinely meet the evaluation criteria for project design at the Department of Education? No member of the CUNY community, the student body, the academic community, or U.S. citizens in general have any idea what actually is happening to improve student success at CCNY based on this description.

- Project Evaluation (35 points): The abstract does not explicitly describe a randomized controlled trial (required) for the project. Instead, CCNY posits (in a nonacademic and passive voice): “The goal is to study whether the intervention increases credit accumulation rates, retention, persistence and graduation rates, and to examine the characteristics of exactly who benefits (and who does not) from the intervention and whether the effects are significant; results will be disaggregated into subgroups to better understand the intervention’s impacts to different subpopulations.” Essentially, all of these research activities may be accomplished with descriptive statistics that have no basis in social scientific research to measure statistically significant effect sizes per the NOFO.

The Department of Education has awarded one of three $7.x million awards to an institution that does not meet the conditions for improved retention rates during the past 5 to 10 years (see Figure 3), has no prior knowledge if the proposed intervention will be scalable in its educational setting (“a 4-year campus setting”), and has no testable hypotheses — “whether…increases” is not a scientific premise — for its proposed grant program. On a 100-point scale, it seems unlikely that a full proposal narrative as summarized in an abstract as sparsely detailed in the PSSG program award notice could muster more than 50 of the 100 points possible in the above four scoring criteria. Nonetheless, institutional researchers and higher education executives are now asked to wait with bated breath for four years (the PSSG 48+ months period of performance) to learn “whether” CCNY/CUNY and its research advocates are able (this time) to provide reliable, valid, and actionable research for the nation’s colleges – in direct contradistinction to the last decade of public evidence from their own data in IPEDS records.

Is the Competitive System for Federal Grants Merit-Based?

We, as institutional research consultants, have no interest or expectations for the CCNY/CUNY PSSG program to pave a new path for the first-year experience and student success in colleges. The CRT conducted by MDRC and other researchers obviously has no measurable reliability or validity — retention rates at the CUNY institutions, individually and as a whole, are in multi-year declines. The same analysis could be written in regard to the other awardees — Georgia State University and Colorado State University Pueblo — two state university systems. Georgia State University was ballyhooed as “the ‘moneyball’ solution for higher education” in 2019 – whereas IPEDS data show that its first-year full-time student retention rate has fallen from 84% in 2018 to 78% in 2022. Perhaps Pueblo, Colorado has struck gold in the search for college student success — we have not investigated how that application won. We only note that CSU did not include a reference to a RCT in its abstract or press release to a campus community that is now subject to a vast experiment. Apparently, the Department of Education plans to happily dole out over $22 million to three institutions that show little regard for the PSSG priorities in their abstracts, informed consent to subjects of social research on their campuses, and/or nationally available statistics on retention (IPEDS).

The question then is: were other applicants more worthy of funding than the national darlings of federal grant reviewers and non-academic print media as “strongly evidenced” by the Department of Education PSSG awards?

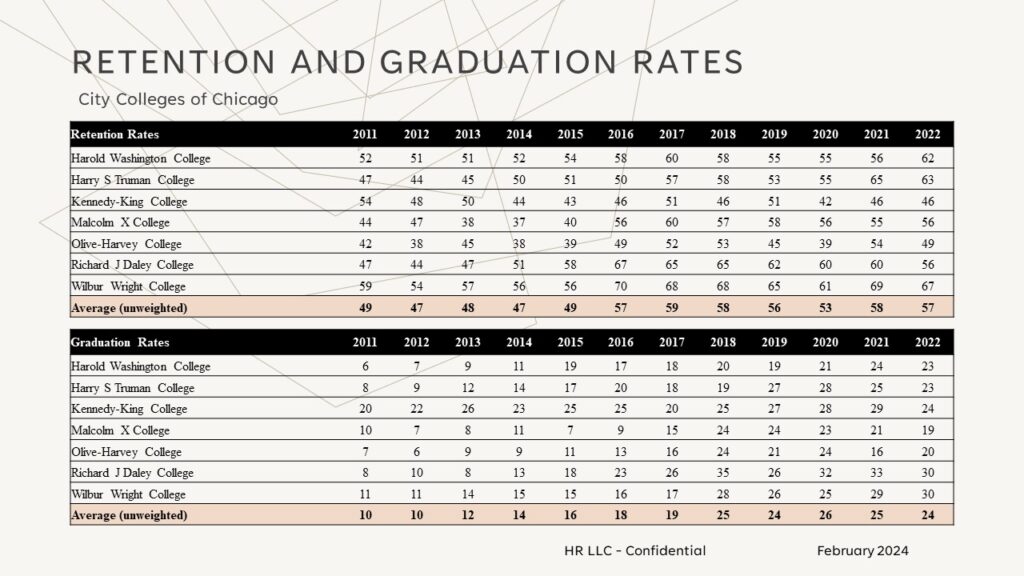

Figure 4 | Community College Student Retention and Graduation Rates at City Colleges of Chicago (CCC)

As Figure 4 (above) illustrates, City Colleges of Chicago (admittedly close to home) has established a remarkable trajectory for improvements in retention and graduation rates over the past decade, the COVID-19 pandemic notwithstanding. Retention rates jumped and have maintained since 2016. Graduation rates have increased incrementally over 12 years — and truly doubled in the past decade (in contrast to claims by CUNY and MDRC). By improving both retention and graduation rates, institutional researchers outside of the City Colleges of Chicago may regard the improvements on the community college campuses as potentially substantive, effective interventions that transcend the usual gimmicks to credential students who proceed to a second year of studies (one-year certificates). In effect, City Colleges of Chicago has possibly implemented on its seven campuses “evidence-based strategies that result in improved student outcomes for underserved students” — the purpose of the PSSG program.

Nevertheless, we may never know because the federal government chose to fund a failed method of intervention that has proven to be ineffective at the local institution, in its own urban community college district, and for the nation as a whole over the past two decades. We are not able to say, one way or the other, if City Colleges of Chicago applied for a PSSG grant. As an institutional researcher, we are only able to say that we have immensely more interest and faith in what has transpired at the community colleges in Chicago than at those in New York City over the past decade. Oddly enough, City Colleges of Chicago already invested in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) and published results in a major higher education research journal in recent years (Hallberg et al., 2023). Research and analysis of the RCT is likely ongoing since six- and eight-year degree outcomes (bachelor’s) will not be available until 2026 at the earliest. In addition, with PSSG funding, the original RCT data could be supplemented with more institutional records and made available to academics and scholars of higher education for years to come to fully measure the significance and effect sizes of evidence-based practices in the district.

It seems that City Colleges of Chicago exemplifies the purpose and the priorities of the PSSG program even before the funding had been defined and announced to the rest of the nation last summer. The Department of Education had an opportunity to enlist a new partner in the search for evidence-based practices to improve college student success and to provide a comprehensive data set for academic researchers to analyze for the discipline of higher education for years to come. Presumably – like CCC – many other colleges, districts, and systems with verifiable and sustained improvements in both retention and graduation rates had something to offer to scientific researchers and the nation with regards to college student success. Instead (seemingly), the Department of Education allowed three reviewers to tank applications from across the nation in order to dump $15 to $21 million in speculative and questionable — if not failed — practices at two (if not three) colleges that have proven to deliver non-replicable results within their own institutions, to their community college districts or state university systems, and for the nation as a whole — for over a decade.

For posterity, the original website and abstracts published by the PSSG:

We encourage other colleges that sought 2023 PSSG Mid-Phase funding to send us their unpublished Abstracts as comparisons with the “winning” abstracts! Email contact@historiaresearch.com.